Since I retired in 2003 I have been much more attached to the Methodist Church than to the Anglican Church. This is partly due to the fact that for most of my ministry I have been a "sector minister", working as an Industrial Chaplain (of which more later), mostly outside the parochial box and therefore to some extent "off the radar" of local clergy. It is also partly due to Anglican liturgy, which because it is so wedded to its traditional language and theological understanding, lacks (to my mind) the flexibility to able to change with changing times. And, of course, the Church of England is now in Covenant relationship with the Methodist Church of Great Britain, which I applaud whole-heartedly! So I used to spend my Sundays in the various churches of the South Kent Circuit of the Methodist Church, leading worship and preaching about six times in a quarter.

However, the more I wrote about the present, the more I realised how far I had travelled since my childhood and youth, and since my ordination in 1968. So the story really begins way back in those days. But the impetus came from Kristiane, a Canadian friend and minister, who once said to me, "Why do people use the word Christ as if it's Jesus' surname?" That single thought has worried me (as dog with bone) ever since, and could be said to have begun in me a journey of understanding that has energised and exercised my mind ever since.

Any journey begins at the beginning, so I had better start with my early life. I was born in Banbury but my parents George and Doris moved to Edgware in north-west London when I was about eighteen inches long. Dad hailed from Prestwich, Mum from Ashton-under-Lyne, and they were fourth cousins - Mum's maiden name was also Blount. Dad had worked at Allen West in Brighton, but was invited in 1932 to join in establising a new company, Switchgear & Equipment Ltd, in Banbury. Mum and Dad married in 1933. I was born in Banbury in February 1938, and after a brief stay in Wolverhampton, by 1939 we had all moved down to Edgware. My early years were spent therefore during World War Two and I have some vivid memories. One is of standing in our back garden watching a dog-fight in the skies until Mum hauled me indoors; another is of being pushed into the hall cupboard where I was squashed between coats, Mum and the milkman, (and a plate of spinach which I was refusing to eat; those moments between the sound of a doodlebug engine stopping and the explosion when it landed; another is of my bicycle decorated for a VEDay fête at my school. Once a bomb landed about 200 yards from the house, blew the back door off its hinges and broke most of the windows at the back of the house - I slept through that one.

Mum and Dad were very different. Dad was a draughtsman by training but an engineer and inventor by instinct. One of his jobs brought him in touch with some emerging African countries where electrical grid systems were being developed. Occasionally he would get a letter with some drawings or blueprints of a grid component, with a request to see if he could find a way of making it cheaper and easier; he always could, and got a reputation for simplifying things. I remember him designing a connector for joining two steel cables, and testing it by lifting a car on a crane. When no-one really believed he could get the connector undone because of the tension involved, he undid it by hand. It was a shame the company held the patent. Any skills I may have in mending things come from Dad. He spent every - every! - evening with his drawing board, making drawings for a friend whose company made electric motors. Mum used to get fed up with the constant scratching of a razor blade on the drawing, when a line of indian ink was in the wrong place. I can hear it now! But - his nightly draughting helped pay my way through school, or so I have always believed.

Which brings me to Dad's car, and the fridge. Fridge first: being in the electrical trade, he could get a discount on electrical items, and he decided one day that we should have a fridge. So he bought one - a German fridge. The controls were in German, the instruction book was in German, and no-one, friends included, spoke any German. Just after the war, German was not popular. So I was commissioned to ask a language teacher at school if he could help us out, and got a fairly brusque brush-off. I imagine we bought a dictionary, because they used that fridge for many years. The car was a similar story. Dad decided to buy a car, so he bought a Daimler. If you know about cars, you may remember that Daimlers had a pre-selector gearbox and a fluid flywheel, precursors of modern automatics. To change gear, you moved the gear lever by the steering wheel to the appropriate gear number, and at the appropriate time, pressed the gear pedal - not a clutch, just a mechanism that effected the change of gear. But somehow Dad never quite got the hang of changing gear, despite his engineering background; I have memories of him stopping at lights, and then starting away on green but still in fourth gear. Sure, the car would pull away, because it had a fluid flywheel like a modern automatic - but oh! so slowly! His driving style was the classic "10 to 2 and don't let go!"

Mum was artistic, while Dad was pragmatic. She'd been a secretary in her early years, and once went to America with her best friend Grace. She sang in a local choral society, and while in her early fifties learned to play the cello, performoing in the Edgware Symphony Orchestra in their concerts.

Later she became involved with John Groom's Crippleage (impossible to use such a word now!) - a marvellous residential centre for disabled women just a mile or so from home. She encouraged them to form a choir, and even to perform one-act plays in front of an audience. Seeing the ladies, some on crutches, taking the roles in a short play was wonderful - Mum gave them a whole new outlook on life. This took up a lot of her energy - I was in my late teens by then - and she regularly got Dad to act as taxi-driver for the choir members. Any skills I may have in playing piano or organ come from Mum.

Like most children in the 1940s I was sent to Sunday School - at least, I think I was. My parents were nominally Methodist, the Methodist Church was a mile and a half away, and the Church of England was round the corner. So I became an Anglican by their convenience. Actually, I became "C of E" because the local Conservative Evangelical parish would have thought "Anglican" a High Church description smacking of popery! Those days are somewhat hazy, and I remember more clearly my early teens when I had graduated - by age if by nothing else - into the Bible Class. This was held weekly in a damp and smelly British Legion hut - no kinder description can be found - and led by two or three adults of whose names and faces I have no memory at all. I and another boy shared the role of pianist, and we sang with gusto hymns from Golden Bells and choruses from the CSSM (Children's Special Service Mission, normally pronounced "syzum", not unlike "schism"!) Chorus Book. Of course, the term Bible Class meant that we were supposed to become familiar with the sacred words of God's Word. So we had "bible searching", which was a competition to see who could find some obscure verse in the shortest time. Like learning your multiplication tables, the practice of hunting through the Bible (always a capital "B") made me familiar with where the books were, but not at all familiar with what they what they were about, which is far more important.

I am reminded of a moment in my teens when the then Rector of Edgware was asked about those who have never heard the Gospel - would they be saved. His answer was, "I know nowhere in the Bible that says they will be saved." That struck me at the time as completely unfair, though, in those days, no-one ever challenged anything the minister said. There was a much greater regard for (fear of?) authority in those times and I would never have dared question the Rector. I suppose my earliest questions about what Christian faith was really about might have begun then but I certainly didn't recognise it.

However, there were a number of truths that I would never have queried. These are the truths that dig deep into the mind and lodge there, hammered in by sermons and talks, by bible expositions and by common agreement. This was the world of what is called Conservative Evangelicalism, where the truth is plain and unvarnished, where questions were taken as doubt and where doubt was a sin. As I read somewhere recently, "You can ask questions so long as you come back to the right answer." The Bible as God's word, the Bible as inerrant as regards salvation, the Bible as historically true, these beliefs were never questioned. The whole purpose of being a Christian was to make other Christians, so saving them from everlasting hellfire. Prayer made things happen, and the Quiet Time with which one started one's day was an absolute necessity. I had a Bible reading scheme devised by the Scripture Union, in which every day began with a Bible passage, an explanation or exhortation, and a prayer. There was, I seem to remember, a slight element of fear of what might happen or not happen if the Quiet Time was not taken seriously.

The single event that, in retrospect, mapped out my future was a conversion experience. It happened just inside the room on the right at the top of the wide staircase in the Central Hall, Westminster, in mid-evening on October 3rd, 1953. I had been invited by a school-friend to a rally at which the preacher was one Joseph Blinco, possibly an associate of the Billy Graham machine. I cannot remember one single word that he said that night, but in some way (and it's difficult to describe this in other words than these) my heart was touched and I "found the Lord." Looking back at my tearful encounter with Jesus, I can only recall the sense of excitement it gave me, together with a feeling that this was somehow more significant than I knew at the time. In those days we called this experience a conversion, and referred thereafter to one's "spiritual birthday". So my life changed, and the single most important objective was to become a good Christian; even my schoolwork took second place.

I was not a confident youth. I had been through a traumatic upgrade from primary school, which was gentle and friendly, and just up the road, to the prep school for Haberdashers, which was also fairly gentle and about five miles away, and then to the main school just yards inside the borough of Hampstead but actually adjacent to a council estate in Cricklewood and a ten mile cycle ride away. The main school was harsh and competitive, and my first year was spent in some indefinable fear and nervousness.

I did fairly well at most subjects, but the transition from primary and prep schools was brusque, and I still hold the record for the highest number of detentions in one term. One boy had nine and was expelled. I amassed fifteen! Detentions were earned for work or behaviour, and mine were equally divided. But I remember one teacher - an ex-RAF officer and unforgettable as a bully who nowadays wouldn't last a week as a teacher - who delighted in tormenting me as the sphinx, probably because I sat and gazed at him while he dictated long essays about history, spelling words like "this" and "king" and ignoring words like "imperial" and "Alexandria". But life went on, and as I entered the sixth form I was studying only French and Music for "A"-level. These two years were comparatively blissful. I was faraway from the bullies, both students and teachers, and the teachers I met with frequently were keen to teach and skilled at it. One happy memory was being the piano accompanist for about fifteen boys playing a variety of pieces on various instruments for a school concert.

At some point I became the leader of the Christian Union and had the responsibility of inviting outside speakers to come to the school every Monday lunch-hour. I had inherited a list of "suitable" speakers, so the task was not too onerous. Paul Delight, one of the teachers, was nominally in charge of the "official school activity", so my responsibilities were limited to invitations and opening the meeting with prayer and a bible reading. Good experience, I suppose, for what came later.

Church in those days was St Andrew's, Broadfields, a daughter church of Edgware Parish Church.

It was a dual-purpose building, with the holy end screened off during the week. On Saturday evenings there was the CYF - Christian Youth Fellowship - a collection of young people in mid-teens, some from the local neighbourhood and some others from Mill Hill, which was about four miles away. I was never quite sure why the Mill Hill group came. But we met for holy stuff, and I can't remember a single thing we ever did or said. Nevertheless it was a nice jolly crowd, and we did get to squat in the Parsonage next door by invitation of the curate, Ian Stevenson. We were all round about the same age, so when we all left to go to college or whatever, the CYF more or less folded.

My Sundays consisted of Morning Prayer, Bible Class and Evensong - three encounters with faith every Sunday. The congregation, like its neighbourhood, was middle-class and educated, and the church was, like its parent, conservative evangelical. This means that we were serenaded by the joys of believing in Jesus, and forcefully warned of the perils of not believing. It was a very black-and-white faith, and no-one ever questioned anything. The Gospel is clear: believe in Jesus and all will be well, for ever. Edgware Parish Church was a member of the Edgware Council of Churches, but at some point left the ECC to form, with Camrose Baptist Church, the New Edgware Council of Churches. Apparently the ECC had invited a representative of the Roman Catholic Church to attend meetings, with mere Observer status, but this was intolerable to the conservative evangelicals, who left and doubtless prayed for us to come to our senses. It was not uncommon to hear prayers in church aimed at persuading God to convert the Catholics to the true faith. And I swallowed all this with ease; it was after all exactly what the Bible said (or so we were led to believe).

One more indication of the narrowness of my home church. Just up the road from our house, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Westminster built a large church building, and Cardinal Heenan went along to consecrate it. This caused outrage in our Church of England parish, and for a couple of weeks before the consecration the whole area was covered with hand-delivered anti-Roman Catholic literature. (This coverage, by the way, included large parts of the area which were almost exclusively Jewish!) My mother, who was ecumenically-minded before the word became popular, was asked to play the organ for the consecration, which she more than willingly did. The Rector of Edgware turned up on her doorstep some time later to reprimand her for her reprehensible behaviour in supporting the heretical papists, and she threw him out. Wow!

Sometime during my later teenage years I was persuaded to think about becoming an ordained minister. I have no idea where this idea came from, nor of who planted the idea in my mind. My mother was pleased with the idea, and my father non-committal; I have always wondered if he would have preferred me to become an engineer of some sort - he had no interest in things religious and I revel in mending things mechanical. My parents' previous interest in my pursuing a career in law was now abandoned.

This happy state of affairs, in which I was content with my Christian assurance of heaven, and not discontent with the vague notion of becoming a minister, lasted through my teens and into National Service. In 1957 I gave two years and a day to the Queen. I occasionally went to church, and while training in Oswestry, went to a Plymouth Brethren church, which was something of an eye-opener. One Sunday morning they were celebrating the Lord's Supper, and at the time of sharing bread and fruit-juice (I doubt it was wine) a loaf was passed round the congregation. I broke off rather a large piece, and spent much of the rest of the service chewing it. Looking back on that incident makes me realise how hard it is for people who don't know how things are done in church to actually make it through the doors for a second time. But for most of the time Sundays were rather like all the other days, and some of my evangelical fervour evaporated as my former Sunday practice changed. However, the idea of ordination never wavered, and twice I found myself on ordination courses at Bagshot Park, then the extravagant headquarters of the Royal Army Chaplains Department.

After National Service, I found myself working for a year in the bookshop of the Scripture Union, in Wigmore Street, London. This was followed by six months as a Stock Checker in a local factory, and six months as a Ward Orderly in Edgware General Hospital. I had wanted to be a hospital porter, but got the job title wrong, and spent six months cleaning bedpans and dishing out hot chocolate and Mackeson to patients. Still, all good experience, one might say. And in the meantime, I had applied to study for a London BD at the London College of Divinity, then in Northwood in north-west London and later to become St John's, Nottingham.

LCD was a theological college in the conservative evangelical tradition, with a fairly rigid ethos. It's a small point, but we were not allowed to visit the pub down the road, we were not allowed to become engaged without permission from our Bishop and the Principal, and wives and fiancées were only allowed in on Saturdays, and on Sundays until the time for Evensong. The choice of the most appropriate college for me to attend was a compromise between the Rector of Edgware, who wanted me to go to one of the Bristol colleges (very conservative evangelical!), and the Bishop of Willesden who wanted me to go to King's College, London (liberal - ugh!). LCD was sort of midway between the two. While we studied the latest biblical scholarship, Christian doctrine, worship, church history and all the other subjects, we made sure that every lecture began with prayers - even to the point of invoking God to return after a double period coffee-break. I remember very little detail about being at LCD. One activity that gave me much pleasure was to be made Organ Scholar, a post I held with neither remuneration nor organ. There was a decent grand piano in the chapel, and I was the designated pianist after Mike Booker (a much better musician that I) left the college. One highlight of that post was to be the pianist when LCD hosted the BBC's Songs of Praise, and I suppose my face must have appeared at some point during the broadcast, but no-one ever told me.

Nothing before this prepared me for the gentle discipline of life in a theological college, where the whole programme of studying was enveloped in a liturgical framework of prayer and worship. One incident stands out, which has stayed with me ever since and has become a feature in any sermon I give about prayer. Students were sent out on placement every week during term-time, and one regular venue for that was Mount Vernon Hospital, about half a mile away. Students would practise their bedside manner, practise taking ward services, and gain useful experience of being around illness and recovery. At one point, there was a child perilously close to dying from leukaemia, and the whole college took to prayer. All-night prayer sessions went on (I was not part of that excess!) and every day or two we would have an update during lunch about the child's condition. There was a profound sense among many of the students that this much prayer would effect a miracle, and so every opportunity was taken to beseech (badger?) the Almighty to intervene. The child died.

The student body was crushed. Among the proponents of the prayer sessions was a deep disappointment, and every argument possible raised to explain away the absence of the miracle that was expected. The gloom lasted for some days. But some of us were more ready to question the premise that prayer works by quantity and much repetition - not the most welcome question to be raised amongst students for whom prayer unlocked the divine purpose.

One aspect of training was what now might be called "work experience", in which all students were sent out about once a week into a local parish, hospital, youth centre or whatever (I cannot now remember) to gain experience of the job of ministry. At one point I was sent up the road, literally, to Mount Vernon Hospital, then (maybe still now) a leading hospital in the treatment of dental plastic surgery. This placement was to prove fortuitous, because a friend and fellow student, Peter Joslin, had connections with MVH which led to us both being roped in to help with their Christmas Show, an ambitious event ably supervised by Rene Ollen, the MVH Welfare Officer and ex-show-biz. So for two or three Christmases, Peter and I were part of the production team - Peter on props, scenery and make-up and me on piano and tape recorder. Great fun, all round. And this is when I met Vivienne, a staff nurse at MVH and later to become my wife.

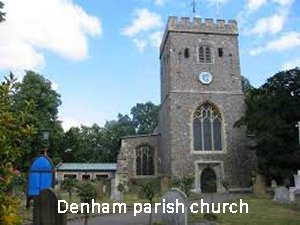

There came the time, towards the end of the third year out of my anticipated four, that I began to get seriously anxious both about my preparedness for the examination for the college diploma but more importantly, about my willingness to continue at LCD. To some extent I felt I was being moulded into a clone of an Oxbridge evangelical minister, and that to do justice to all the training, I would have to change my personality to fit the mould. This is writing with hindsight - I do not think I could have expressed my thoughts then even as clumsily as I just have. I simply felt I wanted a break. So I left with neither tear nor trace. No degree, no college qualification, just a great weight off my mind and an added burden on my mother's. I don't think my father ever quite understood my reluctance to enter engineering in some form. I went to work for Henlys, a car distributor on the Edgware Road, as a delivery driver, driving mostly new Jaguars and Rovers to salesrooms or customers. My fiancée Vivienne was by then a nurse in the Licensed Victuallers National Home in Denham,

which also gave her a bungalow, so my evenings were spent there before going back home for the night. I linked up with the diocese of Oxford (Denham is in Oxford diocese), which allowed me, on the strength of three years at LCD, to become a Lay Reader. The Rector of Denham, Ernie Corr, was kind and understanding, and gave me opportunities to preach and take services in Denham. When eventually we got married in Denham Parish Church, I moved into the bungalow and got a job driving London buses from Uxbridge into central London and around the outer suburbs.

Ernie Corr was an Irishman, laid back to the point of horizontality, who was beloved by everyone for his gentle manner. His theology was unremarkable, personal without being aggressive. Once, when asked about eternal life, he replied, "Well, I'll just leave that to God and get on with the job." The many theological answers he might have given, and he would have been eminently able to do so, were irrelevant to the person asking the question, who was more curious than anxious. Don't sow doubts where none are welcome, but don't fight shy of asking awkward questions.

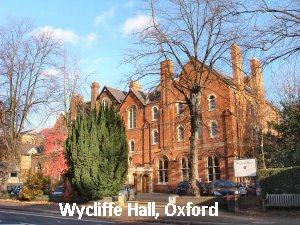

Wycliffe Hall, Oxford, was very different from LCD. There was a more relaxed atmosphere and a more liberal theology. Whereas at LCD there was a continual sense of being driven, at Wycliffe no-one much minded if you played croquet on the lawn one morning provided that work and duties were done. And at Wycliffe I was Piano Scholar with an organ, and (I think) about £50 a year. One of the real gifts of being at Wycliffe was the fact that the college had rooms to let to students from other colleges - Paying Guests, or as we called them, PGs. During my time there we enjoyed the company of an Armenian Archimandrite, two American Episcopalian priests, a French Abbé and others I cannot remember. It made for a wonderfully eclectic mix, and because Wycliffe was not so divided into conservatives and others (or right and misguided, as LCD might have put it), the sense of community was very strong.

Vivienne worked as a Staff Nurse on the private ward of the Radcliffe Infirmary. We began our stay in Oxford in an upstairs flat in a house which belonged to St John's College and was rented out to two Russian ladies who had fled Russia many years before.

They were terribly anxious about keeping on the good side of St John's College, and were therefore insistent to the point of neurosis that we should not damage the flat in any way (even drawing pins were banned) in case the authorities at St John's might eject them. Living there even for a few months was almost oppressive, so we were grateful to be offered a downstairs flat in a college house in Norham Gardens. Here we stayed for a year or so, with occasional parties thrown in our large lounge, trying not to disturb one of the college tutors who lived above. And here our daughter Karen was born in 1968, not even a toddler when we eventually moved out.

I warmed to the research needed for essays and the sense of beginning to understand what Christianity was about - still an undisturbed evangelical, but without the obsessive pressure. Over the course of two years, I studied various topics under the usual headings - New & Old Testament Studies, Christian Doctrine, Church History, Liturgy and so on. But rather than lectures, we were given a topic and about three weeks to research the subject and write an essay. I thrived on this way of learning, and enjoyed every moment spent in the Library, digging into academic journals and discovering ideas that excited me. Tutorials, one to one with the tutor, were enjoyable and satisfying - I could have a real conversation about something and come away knowing that I had mastered at least something that day. In all my three years at LCD, where we had to write at least two essays a week, the only feedback I remember was from Michael Green, who wrote on one returned essay, "You have not yet learned to think theologically." It has taken me many more years to understand what he was driving at. However, in the background there was always the need to pass the exams and actually get to wear the clerical collar. When I am ordained, I convinced myself, things would sort themselves out. I never did take the BD degree, but took (and passed) the London University Diploma in Theology (roughly equivalent to a first degree) plus appropriate bits of God's Own Exam, otherwise known as the General Ordination Examination.

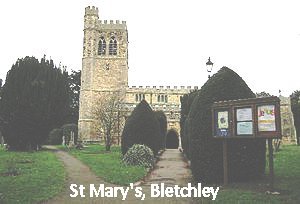

In 1968 I set out as curate in the parish of Bletchley and found myself locked into parish routines that made it difficult, or dare I say unnecessary, to continue studying any more than what was needed for sermon preparation. There was a daughter church, St Frideswide (no, I'd never heard of her, either!), which was in Water Eaton, part of the parish on the banks of the Grand Union Canal. I well remember with affection our one and only welcome visit; Vic and Audrey Kirkbride, both members at the parish church and members of the choir, knocked our door shortly after we'd moved in, and greeted us warmly. They became firm friends. Their welcome was so much more encouraging than the Rector's, who took me to St Frideswide's, gave me a key, and said, "I'll come down every other week and take a communion service." And left me to get on with it. It wasn't too log before I realised that I was not going to get any training from him!

However, I found that I had enough knowledge to do what I thought was needed. The job of being curate was repetitive in many ways - visiting, preaching and meetings - and my brain seldom got itself into gear with deeper questions. Looking back, I am conscious of getting by with tried and tested ideas, and never wishing to push out any boats that might make demands. The job of curate in Bletchley turned out to be mostly looking after the small village of Water Eaton and the rapidly expanding Lakes Estate, a new development for victims of London overspill, with very little training from the Rector despite his being known as a "Training Incumbent". Apparently the Rector missed that point. Visiting? Preparing sermons? Taking services? For me it was a matter of "make it up as you along". The diocese laid on Potty Training (Post-Ordination Training, or POT) once a month, to which about twenty recently ordained clergy went along, and this was well organised by the late and well-regarded Canon Wilfrid Browning in Oxford. I probably learned more from that group than I ever did in my "training parish". [Incidentally, before ordination there were similar training sessions, known by some as Nappy Training - Not a Proper Priest Yet!] And while we were in Bletchley, our son Kevin was born in 1971. It was also the time when Mum died from cancer; she had been diagnosed with breast cancer when I was young but had been in remission for many years. For many years I thought I had been evacuated to live with my grandmother near Sleaford, but learned much later that Mum had been in hospital for several weeks. These were things we never talked about in those days. She lived to see Karen but sadly not Kevin.

So I ploughed my own furrow, made my own mistakes, and probably learnt much less that was expected. The parish staff consisted of the Rector, myself as Curate and two parish workers, one experienced and one novice. So it was two seasoned and two novice folk who had responsibility for the spiritual welfare of the parish. As a staff group we got on remarkably well. Staff meetings were affable, consisting mostly of diary planning and other practicalities. At 5.30pm every day we would meet to say Evensong together, and we enjoyed each other's company. We two novices were tasked with the small youth group, which is the usual fate of the younger staff of a parish, regardless of having the necessary skills (or, in my case, lack of them).

Every so often I would be invited to preach in the parish church, and on one occasion during my first year as a curate, there occurred one of those incidents that causes complete panic for a second until adrenalin takes over. Enoch Powell had fairly recently delivered his "rivers of blood" speech, which was still causing alarm in the country. While preaching about (I think) the Good Samaritan, I mentioned Mr Powell, whereupon Bill Moyes, a normally mild-mannered and respected citizen, rose from his seat, declared in a loud voice that "I didn't come to church to hear party politics!" and stormed out of church, banging the huge mediaeval doors as he went. The silence was audible, until I recovered myself and carried on. Somewhat nerve-shredding at the time, but later Bill and I had a drink together and he confessed the words "Enoch Powell" had woken him up.

In Bletchley, in addition to the myriad Good Things I didn't learn, one thing I did learn was Ecumenism. We had heard the word bandied around in college, but it was never suggested that we should take it seriously. We were the Church of England, for God's sake! However, Bletchley in 1969 was incorporated into the New City of Milton Keynes, with much fanfare and excitement. The Bishop of Oxford appointed an Ecumenical Officer for Milton Keynes, Revd Peter Waterman, and his task was to establish good working relationships amongst the clergy and ministers of Bletchley, Fenny Stratford, Stony Stratford and the other towns in the designated area, and to bring together all the denominations in planning the shape of the future church in the city. I found myself talking with Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists and Roman Catholics, and wonder of wonders, we all seemed to get on well with each other!

The Baptist minister, Leslie Jell, introduced me to the New Town Ministers' Association, a gathering of ministers and clergy from the forty or so New Towns up and down the country. This at last opened my eyes to a much wider understanding of ecumenism - how to adapt the traditions of the various denominations so as to be able to share not just worship but also insights and experience from their respective histories. I was beginning to see beyond the first hilltop to the mountain ranges in the distance.

The NTMA held an annual conference, which assembled a couple of hundred ministers and lay people. When I asked the Rector if I could take that time off, he said, "Well, I suppose you'd better get this ecumenism out of your hair early on!" So much for the Ecumenical Imperative! This was Ecumenism in the raw: at one of the closing Eucharists, a much-loved RC priest from Skelmersdale made a show of attending but not receiving the bread and wine, bearing the pain of disunity very visibly and to the pain of the rest of us. Our discussions were often highly critical of the resistance of denominations to any form of change.

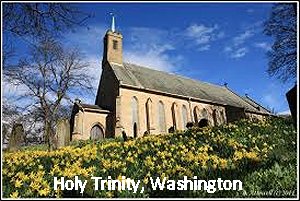

My second curacy was in Washington Co Durham (CD, not DC!). This was a Group Ministry of five parishes, with an Area of Ecumenical Experiment (AEE - nowadays known as a Local Ecumenical Partnership (LEP)) within one parish - five parishes sharing the work but linked together by formal agreement, with a central Group Council in addition to the Parochial Church Council of each parish. Oxclose was the AEE, in which the CofE and the URC were formal partners. Washington was still being expanded from a series of urban villages into a single New Town, so much of my time was spent visiting newcomers and the recently arrived. One of my chief allies in this was the Community Development Officer from the Development Corporation, who was extremely supportive of my work as I was of his. In NTMA I began to realise the potential for ecumenical working and the sheer joy of discovering how much the various denominations have in common. NTMA conferences were tackling some thorny issues concerning the Church in green field sites, co-operation between denominations at local and at hierarchical levels, and how to ensure continuity of ecumenical posts when an incumbent leaves. In Washington I began to find partnership outside the church more constructive and better understood than inside it. This point will be made again later. The CDO and I worked quite closely in trying to integrate newcomers into Washington, and we shared a lot together about each other's work.

So again I was working ecumenically, though not so closely with other denominations. But my next appointment was as a Team Vicar in St Andrew's, Chelmsley Wood, a new town (but not under the New Towns Act) sitting on the M6 between Coventry and Birmingham. This was an Anglican-Methodist Church, and the Team consisted of a Team Rector, three Team Vicars, a Methodist Minister, and a Sikh youth leader. Since the first turf was cut for this huge development which would re-house tens of thousands from Birmingham city, the church - at first without a building - was at the centre of this human migration. Here I began to learn that ecumenism was not simply a matter of ecclesiastical joinery - bringing the various churches into a greater unity, although that is a central theme - but also bringing the world into a greater unity. Was it Hans Küng who said, "The churches must come together so that the nations may come together so that the world may come together"?

Here we had our second notable welcome visit. Helena Hammond, Mrs H to most people, was an elderly London eastender with a glorious cockney accent and a wonderfully cheery disposition. She turned up at our door one day, and when I answered the door I was greeted with, "'Allo, I'm Mrs 'Ammond your baby sitter", by which time she was in the kitchen clutching an apple pie! Mrs H became our children's closest grandmother and on very many occasions spent the evening looking after them and knitting endless garments. She lived ten floors up in a block of flats overlooking the M6, and spent most of her time looking out of the window through a large mirror on the wall, knitting and watching the traffic on the motorway.

Karen was old enough to begin school here, at Bishop Wilson Church of England Primary School. So she dutifully went along to school with Vivienne on her first day. We've come to know Karen's independent spirit over the years, and on this first day, arriving at the school gate, she turned to Vivienne and said, "All right, Mummy, you can go home now." Such confidence at such an early age!

Originally the new congregation in this new parish used this new church school for Sunday worship, but the predictable desire for its own building resulted in a multi-purpose Church Centre. Sunday worship followed Anglican services for four months of the year, Methodist services for four months, and what were called Ecumenical services for the remaining four months. At least, that is how I remember the pattern. Whatever the detail, it offered a variety of styles, and in those relatively early days of my encounter with the ecumenical movement (as it is called), this was a significant advance and nothing to do with "getting it out of my system" as the Rector of Bletchley had called it. Indeed, I began to think that this was the most natural way of working for the Church in the future.

2022 update - we'd just been to the Caravan Show at the NEC and took time to drive around "The Wood" as it's now called. The original building for St Andrew's is now the property of the Seventh Day Adventist church, and both Bishop Wilson School and St Andrew's Church have moved to new premises in another part of town. Progress, I hope.

My team rôle was relating to the community organisations of Chelmsley Wood, and that was as much Ecumenism as anything the churches did together. I need to explain this: the Greek word

oikos means "house, abode, dwelling", and it is the root of our words Economy (how we do business together), Ecology (how we care for the planet) and Ecumenism (how we relate to each other). The discovery of this simple fact those many years ago was like unwrapping a gift, switching on a light in a dark place, and it opened my eyes to something new: the Christian imperative is not about getting people into the Christian faith, but much more about getting the Christian faith into the real world that people live in.

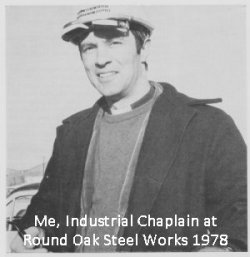

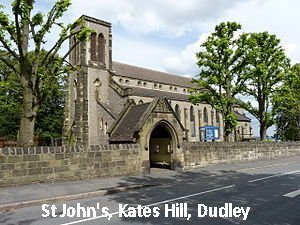

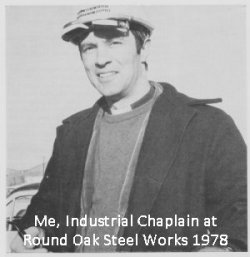

In 1976, having been a curate twice and a team vicar once, I went into Industrial Mission. The new Black Country Urban Industrial Mission was being set up across the four boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, West Bromwich and Wolverhampton. There was a vacancy in Dudley, and we moved across in 1976. Over several years the BCUIM team grew to about eight ministers, some part-time, and the BCUIM Council included Anglican, Methodist, United Reformed, Baptist, Roman Catholic and Quaker representatives. This was ecumenism in practice, and I rejoiced in this way of sharing the gifts of our different traditions. It was not always easy - there were tensions about the work we were each doing across the Black Country, but underneath was a strong sense of common ownership of the work.

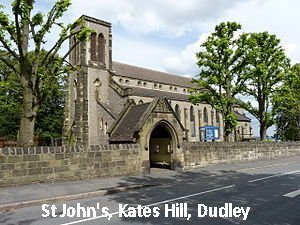

In Dudley I was attached to the parish of St John, Kate's Hill, a parish of about 14,000 people. It was mixed socially, with large areas of both council and private housing. I was there during the incumbencies of two vicars, and we more or less shared the duties of ministry in terms of Sunday services and funerals. (Incidentally, not until I had left the parish did I learn that one of my ancestors, an iron worker in the 1800s, was married in St John's, and another Blount was buried in the overgrown churchyard behind the church.)

The church building was on what had been the smoky side of the hill in those dark days of foundries and forges, many of them in people's back yards. There was much terraced housing and narrow streets. Our house was on the other side, (dare I say?) the middle class side. A vicar in the 1920s had tried to attract folk from "the smoky side" by setting up a Sunday afternoon service (no collection would be taken!) for "those who have no Sunday clothes". I don't know if it succeeded, but there were very few from "the smoky side" when I was there.

St John's was a middle of the road church, with nothing for young people, so there were very few young people! Vivienne and the children found a welcome at St Matthew's Church in Tipton, an evangelical church a couple of miles from home. Without the far more interesting work in Industrial Mission, I would never have survived the stress, effort and sheer frustration of being an incumbent. It would have pushed my impatience to breaking point.

But visiting a steelworks and three engineering companies every week was far more life-enhancing, and gave me a sense of being grounded in the long-established community of the Black Country, which in the early eighties went through the pain and bereavement that is associated with recession and the closing of places of work. Eventually the steelworks closed, and the site bought as an Enterprise Zone, eventually becoming the Merry Hill shopping mall, known locally then as Merry Hell. I tried hard to persuade the Richardson brothers, who bought the former steelworks, to include a chaplaincy, but while they were supportive of the idea, eventually their economics didn't allow for such an initiative.

St John's Church was closed some years after I'd left, because it was unsafe. I remember a story about a bell falling through the tower floor and narrowly missing someone below. Somewhat predictably, its closure attracted more attention than it had ever had before, and a Save St John's group was set up, still going strong. The building is becoming now a community hub.

Industrial Mission - or as it is nowadays more frequently called, Workplace Mission, in order to reflect the changing economic landscape of the country - was very different from parish life. It was a ministry amongst people at work, and in one sense a public relations exercise. Most of the people I met had no detectable sense of God or faith, most had seldom if ever been in a church building, and I did not need much of my acquired theology to exercise a ministry amongst them. Conversation was most often about the work they were doing, and incidentally answering the question of why I was there at all. Immensely satisfying work, but my theology had been parked in a lay-by for almost twenty years. I understood perfectly well that I was working ecumenically (in both the churchy and the wider senses), and my work took me into various companies and work-related organisations. I was continually meeting up with trade unions, chambers of commerce, local government and a host of passing contacts - the real world indeed. The problem Industrial Mission faced was getting the churches to listen and take notice of anything we said.

There was - and probably still is - a real problem in understanding the work of Industrial or Workplace Mission, not in workplaces but in the churches. In workplaces, in my own experience, there were few conversations with non-church people about faith in God, but many more about "Church" . This is why I referred to the work of an Industrial Chaplain as in part a public relations exercise among people, many of whom had no experience of church. This was a ministry of accompaniment, walking alongside people at work and trying to understand the things that most concerned them - things like working long hours, the security of their job, the pressure to meet deadlines, whether in a recession their children would find work, and a host of those practical problems that everyone has. I was a sounding board, a neutral counsellor, and, oh! by the way, I'm from the Church. But that was valued by the people we met, who seemed to understand instinctively that the Church would be supportive of them even if they had little idea of how or why that might happen.

In the churches, however, we were asked about how many people we met were church-goers, did we hold worship services in factories (No!), and what sort of response did we get when we talked about God. There was an expectation that we would encourage "bums on pews", whereas we were referring to our work as "pre-evangelism", opening up some first-time dialogue with people we met - which, incidentally, is almost exactly how Industrial Mission (IM) began in Sheffield after World War Two. IM was the only chaplaincy work that was wholly funded by the Churches, and when Church finances began to get strained, IM was one of the first non-parochial activities to be chopped. On one occasion, when my appointment was under threat from lack of funding, my bishop suggested that I might spend some of my time trying to raise funds for my own job! It is extremely sad that so many IM posts were not renewed when a chaplain moved on. Even though the accepted Guidelines for Industrial Mission made much of continuity in IM posts, most Church leaders seemed unable to commit resources for a long-term IM strategy in any particular place, and one Anglican bishop even chopped the funding for an ecumenical IM post that belonged to another denomination!

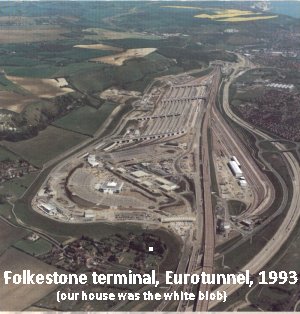

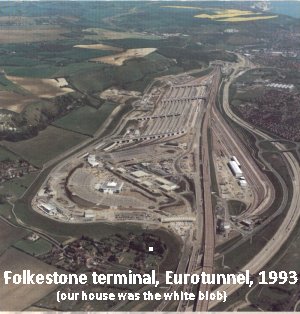

Fourteen years later, in 1989, I moved down to Folkestone to begin work as - and I quote the full title - "Industrial Chaplain to Folkestone and Dover with special reference to Eurotunnel developments." The main focus of the work was with Eurotunnel UK and I was there for five years before the tunnel opened and for eight years afterwards. I was housed by the Church of England and my stipend was met equally by the Baptist, Methodist and United Reformed Churches. Cross-funding, as it is termed, was then a fairly uncommon way of creating ecumenical posts and it worked extremely well for the first five years. Then, when the post came up for renewal, the Baptist Church pulled out, probably because IM is not primarily evangelistic, and the funding was then shared between the Anglican, Methodist and United Reformed Churches. The only (slightly tongue-in-cheek here) down-side was that I found myself invited to meetings of all three denominations.

This job, as a team member of Kent Industrial Mission, was truly an ecumenical appointment. The support I received from each was generous, and for the first few years I spent most Sundays in churches across Kent, talking about the Channel Tunnel and its significance for life and faith. During all this time I was becoming increasingly glad that I was not tied to one denomination and had considerable freedom to travel between churches of different beliefs and traditions. Whilst I recognised that I was able to work only with the Bishop's Licence, and therefore subject to the disciplines of the Church of England, nevertheless in my everyday working I was more aware of serving within the Church of God than within the Church of England.

One significant up-side was that I inherited links between churches in the south-east corner of Kent and churches along the French coast between Dunkerque, Calais and Boulogne. Over those fourteen years we had many visits each way, with real friendships being built. The ecumenical mix was fascinating and rewarding: Anglican, Methodist, Baptist, Salvation Army and Roman Catholic on the Kent side, and Eglise Réformée, Catholique, Anglican and Armée du Salut on the French side. There were already strong links between the Diocese of Canterbury and the Diocèse d'Arras, and also between the Diocese of Canterbury and the Evangelische Kirche Deutschlands around the town of Lörrach, near Basel. So I had a great many contacts with churches in France and Germany to add to my contacts with churches in Kent. Again a few occasions stand out: the RC Bishop of Arras presiding at a communion service in a chapel of Canterbury Cathedral; being offered half of his wafer by Alain Depreux, a French priest who didn't want us to be left out of taking full part in a Mass in Arras cathedral; taking part in numerous services in France and Germany - and in all of these, there was no problem in my being Anglican, or Protestant. This reminds me of an occasion in Austria, taking part with friends in an ecumenical vigil one Saturday. When everyone was invited to the next day's Sunday Mass in the large Catholic church, I asked my Catholic hosts if there would be a problem with my being Anglican. "Oh no," they replied, "that's a question they'd only ask in Rome!"

I began to look forward to the end of my time with Kent Industrial Mission with interest and some concerns. Vivienne and I had grown apart over the years, and we agreed to separate around Christmas 2000. I ended my time with the Kent Industrial Mission on my 65th birthday in 2003 and began what is laughingly called retirement. But towards the end of that time I had been able to spend four months at the Ecumenical Institute of the World Council of Churches at Bossey, near Geneva. This was a rather less than intensive sabbatical, which allowed me to pursue some studies in ecumenism with forty other students from all over the world.

It was almost like going back to college. Morning and evening prayers, lectures all morning and private study in the afternoon and evening, and a large library to explore. So from September to December 2000 I was again a student with the requirement to produce two fairly substantial essays on subjects of my choice.

My essays were entitled "The Pilgrim People of God - Cloud and Fire in Today's Church" and "The Church across national borders (with special reference to European Churches)". The first attempted to reflect on the image of the wandering People of God, able to settle and move on as God's purpose becomes clear, and was based on what might be my favourite passage of scripture, Numbers 9: 15-24. It is almost tediously repetitive in describing how the Israelites camped and decamped according to where the cloud and the fire moved and stopped, and I used this image to express my concern that the Church of today has become so structured and bogged down in its traditions and its buildings that it cannot possibly follow a God who moves on.

The second essay picked up an interest in Church Twinning that I had developed over many years, which came more into prominence during my years in Folkestone with all my European links. At that time there were probably forty or more town twinning links between towns in Kent and in mainland Europe, and I was keen to encourage churches either to set up their own links, or preferably become engaged with the town twinning. At one point I became secretary of the Kent Association of Twinning Organisations, a committee that tried to link together the many town twinnings in Kent. Several times I took a display stand about Church Twinning to the German

Kirchentag (www.kirchentag.org.uk) and even wrote a book called "European Church Partnership - A User's Guide". To be able to sit in Bossey at the feet of Emilio Castro, a leading ecumenist of the 20th Century and a past General Secretary of the WCC, was a privilege and an absolute joy, especially when he asked if he could use something I'd written in his new book.

Looking back over thirty-five years of my active ministry, I am quite surprised that I did not give more time to thinking about theology. But life was fairly hectic, keeping lots of balls in the air, and spending most of the time doing, doing, doing. It was a fairly straight-forward job, with mostly regular events and duties shaping my weeks. But when I retired in 2003, everything began to change.

Retirement has offered me the time to study some more, read books I'd bought long ago but never read, and to find a local church which might offer me a sense of community, of family. This last came about somewhat unexpectedly much later. At first, being now on my own, I found myself in a flat in Folkestone with lots of time to fill. So I took on the role of Ecumenical Officer for part of the diocese of Canterbury, and continued with European Partnerships Officer as before. Feeling the need to get away from Church of England services, I began taking more services for the local Methodist circuit of seven churches - some town, mostly village. I had previously been on the Preaching Plan of the Methodist Church in Dudley, so this was nothing new. Having been what is known as a Sector Minister, I was (fortunately!) outside the parish loop, and was seldom asked to fill gaps in local Church of England churches. I thoroughly enjoyed preparing worship, as it were, from scratch, without so much need to follow prescribed patterns from a book. Another thoroughly enjoyable activity was chaplaincy on cruise ships, and you can read all about that

here.

I was chaplain on sixteen cruises over nine years, fourteen of which were with Fred Olsen Cruise Lines. Somewhere in the FOCL website is mentioned "interdenominational church services", and I was always keen to offer what I called "ecumenical worship". There are extensive resources for worship planning if you search for them, and I spent a great deal of time designing worship using words and music that most people may never have come across. Some of these are

here. There was always a Sunday morning service, and the congregation might number 150 or more. Doubtless part of that is simply that the church service was the only 'entertainment' on offer that early on a Sunday!

However, I did receive sufficient comment of appreciation to continue using unfamiliar liturgy. We get so used to what is repeated Sunday after Sunday that to hear something new demands a bit more attention to what we're actually saying. I played the piano myself, which allowed me to find new hymns as well as new liturgy. On the first long cruise I started having a daily morning service as well, just a fifteen-minute hymn-reading-prayer-hymn. This also seemed to be appreciated.

However, the single best thing I did was to move in with Lesley after the second long cruise in 2012. We'd known each other at a distance through the cross-Channel work I had been engaged in - me in Folkestone and Lesley in Ashford - and she had been on her own for about the same time as I had. Every so often we used to go to the cinema with a pizza afterwards, and at some point the idea of moving in with her was mentioned. We were married in October 2013 in our local Methodist Church.

The Folkestone and Ashford Circuits had been amalgamated earlier, so now I had eighteen churches to conduct worship in, often using some of the cruise services. But I also began to read some of the books that I had bought over the years, and began to ask questions that I had hidden for so long. This led me to devise study courses for sharing around the Circuit, and I found groups of folk who were not unwilling to think outside the box. I have to declare that my faith now is light years from the faith I digested from my youth, and if you have the stamina, carry on reading

The Revolution within the Revelation.

In July 2019 we spent a few days in Sawley, a small village just outside Clitheroe in Lancashire, looking down a list of houses we'd seen for sale. Over several months we had talked about moving away from Ashford, cutting back on some of the networks we'd become attached to, but also because Ashford is becoming a much larger commuter town. We needed a change, and a chance to enjoy retirement in more pleasant surroundings. In July 2020 we moved into our new home in Low Moor, a part of Clitheroe which in former times boasted an enormous cotton mill and rows of back-to-back terraced houses which are still here but well up-graded. In those days, Low Moor was quite separate from Clitheroe, but now is fully part of the town (except for those with long memories).

It rains! The Pendle hills in this Ribble valley apparently have a strong effect on weather patterns, so we get more rain here than elsewhere. However, the countryside is beautiful, although wild and bleak in places. Single-track roads take us into valleys where we find tiny hamlets and certainly more sheep than people. Country pubs abound! We've found a church (URC) where the welcome is friendly and the sermon is (usually) worth listening to. What else could we wish for?

RGB 2022

Later she became involved with John Groom's Crippleage (impossible to use such a word now!) - a marvellous residential centre for disabled women just a mile or so from home. She encouraged them to form a choir, and even to perform one-act plays in front of an audience. Seeing the ladies, some on crutches, taking the roles in a short play was wonderful - Mum gave them a whole new outlook on life. This took up a lot of her energy - I was in my late teens by then - and she regularly got Dad to act as taxi-driver for the choir members. Any skills I may have in playing piano or organ come from Mum.

Later she became involved with John Groom's Crippleage (impossible to use such a word now!) - a marvellous residential centre for disabled women just a mile or so from home. She encouraged them to form a choir, and even to perform one-act plays in front of an audience. Seeing the ladies, some on crutches, taking the roles in a short play was wonderful - Mum gave them a whole new outlook on life. This took up a lot of her energy - I was in my late teens by then - and she regularly got Dad to act as taxi-driver for the choir members. Any skills I may have in playing piano or organ come from Mum.

However, there were a number of truths that I would never have queried. These are the truths that dig deep into the mind and lodge there, hammered in by sermons and talks, by bible expositions and by common agreement. This was the world of what is called Conservative Evangelicalism, where the truth is plain and unvarnished, where questions were taken as doubt and where doubt was a sin. As I read somewhere recently, "You can ask questions so long as you come back to the right answer." The Bible as God's word, the Bible as inerrant as regards salvation, the Bible as historically true, these beliefs were never questioned. The whole purpose of being a Christian was to make other Christians, so saving them from everlasting hellfire. Prayer made things happen, and the Quiet Time with which one started one's day was an absolute necessity. I had a Bible reading scheme devised by the Scripture Union, in which every day began with a Bible passage, an explanation or exhortation, and a prayer. There was, I seem to remember, a slight element of fear of what might happen or not happen if the Quiet Time was not taken seriously.

However, there were a number of truths that I would never have queried. These are the truths that dig deep into the mind and lodge there, hammered in by sermons and talks, by bible expositions and by common agreement. This was the world of what is called Conservative Evangelicalism, where the truth is plain and unvarnished, where questions were taken as doubt and where doubt was a sin. As I read somewhere recently, "You can ask questions so long as you come back to the right answer." The Bible as God's word, the Bible as inerrant as regards salvation, the Bible as historically true, these beliefs were never questioned. The whole purpose of being a Christian was to make other Christians, so saving them from everlasting hellfire. Prayer made things happen, and the Quiet Time with which one started one's day was an absolute necessity. I had a Bible reading scheme devised by the Scripture Union, in which every day began with a Bible passage, an explanation or exhortation, and a prayer. There was, I seem to remember, a slight element of fear of what might happen or not happen if the Quiet Time was not taken seriously.

I did fairly well at most subjects, but the transition from primary and prep schools was brusque, and I still hold the record for the highest number of detentions in one term. One boy had nine and was expelled. I amassed fifteen! Detentions were earned for work or behaviour, and mine were equally divided. But I remember one teacher - an ex-RAF officer and unforgettable as a bully who nowadays wouldn't last a week as a teacher - who delighted in tormenting me as the sphinx, probably because I sat and gazed at him while he dictated long essays about history, spelling words like "this" and "king" and ignoring words like "imperial" and "Alexandria". But life went on, and as I entered the sixth form I was studying only French and Music for "A"-level. These two years were comparatively blissful. I was faraway from the bullies, both students and teachers, and the teachers I met with frequently were keen to teach and skilled at it. One happy memory was being the piano accompanist for about fifteen boys playing a variety of pieces on various instruments for a school concert.

I did fairly well at most subjects, but the transition from primary and prep schools was brusque, and I still hold the record for the highest number of detentions in one term. One boy had nine and was expelled. I amassed fifteen! Detentions were earned for work or behaviour, and mine were equally divided. But I remember one teacher - an ex-RAF officer and unforgettable as a bully who nowadays wouldn't last a week as a teacher - who delighted in tormenting me as the sphinx, probably because I sat and gazed at him while he dictated long essays about history, spelling words like "this" and "king" and ignoring words like "imperial" and "Alexandria". But life went on, and as I entered the sixth form I was studying only French and Music for "A"-level. These two years were comparatively blissful. I was faraway from the bullies, both students and teachers, and the teachers I met with frequently were keen to teach and skilled at it. One happy memory was being the piano accompanist for about fifteen boys playing a variety of pieces on various instruments for a school concert.

It was a dual-purpose building, with the holy end screened off during the week. On Saturday evenings there was the CYF - Christian Youth Fellowship - a collection of young people in mid-teens, some from the local neighbourhood and some others from Mill Hill, which was about four miles away. I was never quite sure why the Mill Hill group came. But we met for holy stuff, and I can't remember a single thing we ever did or said. Nevertheless it was a nice jolly crowd, and we did get to squat in the Parsonage next door by invitation of the curate, Ian Stevenson. We were all round about the same age, so when we all left to go to college or whatever, the CYF more or less folded.

It was a dual-purpose building, with the holy end screened off during the week. On Saturday evenings there was the CYF - Christian Youth Fellowship - a collection of young people in mid-teens, some from the local neighbourhood and some others from Mill Hill, which was about four miles away. I was never quite sure why the Mill Hill group came. But we met for holy stuff, and I can't remember a single thing we ever did or said. Nevertheless it was a nice jolly crowd, and we did get to squat in the Parsonage next door by invitation of the curate, Ian Stevenson. We were all round about the same age, so when we all left to go to college or whatever, the CYF more or less folded.

LCD was a theological college in the conservative evangelical tradition, with a fairly rigid ethos. It's a small point, but we were not allowed to visit the pub down the road, we were not allowed to become engaged without permission from our Bishop and the Principal, and wives and fiancées were only allowed in on Saturdays, and on Sundays until the time for Evensong. The choice of the most appropriate college for me to attend was a compromise between the Rector of Edgware, who wanted me to go to one of the Bristol colleges (very conservative evangelical!), and the Bishop of Willesden who wanted me to go to King's College, London (liberal - ugh!). LCD was sort of midway between the two. While we studied the latest biblical scholarship, Christian doctrine, worship, church history and all the other subjects, we made sure that every lecture began with prayers - even to the point of invoking God to return after a double period coffee-break. I remember very little detail about being at LCD. One activity that gave me much pleasure was to be made Organ Scholar, a post I held with neither remuneration nor organ. There was a decent grand piano in the chapel, and I was the designated pianist after Mike Booker (a much better musician that I) left the college. One highlight of that post was to be the pianist when LCD hosted the BBC's Songs of Praise, and I suppose my face must have appeared at some point during the broadcast, but no-one ever told me.

LCD was a theological college in the conservative evangelical tradition, with a fairly rigid ethos. It's a small point, but we were not allowed to visit the pub down the road, we were not allowed to become engaged without permission from our Bishop and the Principal, and wives and fiancées were only allowed in on Saturdays, and on Sundays until the time for Evensong. The choice of the most appropriate college for me to attend was a compromise between the Rector of Edgware, who wanted me to go to one of the Bristol colleges (very conservative evangelical!), and the Bishop of Willesden who wanted me to go to King's College, London (liberal - ugh!). LCD was sort of midway between the two. While we studied the latest biblical scholarship, Christian doctrine, worship, church history and all the other subjects, we made sure that every lecture began with prayers - even to the point of invoking God to return after a double period coffee-break. I remember very little detail about being at LCD. One activity that gave me much pleasure was to be made Organ Scholar, a post I held with neither remuneration nor organ. There was a decent grand piano in the chapel, and I was the designated pianist after Mike Booker (a much better musician that I) left the college. One highlight of that post was to be the pianist when LCD hosted the BBC's Songs of Praise, and I suppose my face must have appeared at some point during the broadcast, but no-one ever told me.

which also gave her a bungalow, so my evenings were spent there before going back home for the night. I linked up with the diocese of Oxford (Denham is in Oxford diocese), which allowed me, on the strength of three years at LCD, to become a Lay Reader. The Rector of Denham, Ernie Corr, was kind and understanding, and gave me opportunities to preach and take services in Denham. When eventually we got married in Denham Parish Church, I moved into the bungalow and got a job driving London buses from Uxbridge into central London and around the outer suburbs.

which also gave her a bungalow, so my evenings were spent there before going back home for the night. I linked up with the diocese of Oxford (Denham is in Oxford diocese), which allowed me, on the strength of three years at LCD, to become a Lay Reader. The Rector of Denham, Ernie Corr, was kind and understanding, and gave me opportunities to preach and take services in Denham. When eventually we got married in Denham Parish Church, I moved into the bungalow and got a job driving London buses from Uxbridge into central London and around the outer suburbs.

They were terribly anxious about keeping on the good side of St John's College, and were therefore insistent to the point of neurosis that we should not damage the flat in any way (even drawing pins were banned) in case the authorities at St John's might eject them. Living there even for a few months was almost oppressive, so we were grateful to be offered a downstairs flat in a college house in Norham Gardens. Here we stayed for a year or so, with occasional parties thrown in our large lounge, trying not to disturb one of the college tutors who lived above. And here our daughter Karen was born in 1968, not even a toddler when we eventually moved out.

They were terribly anxious about keeping on the good side of St John's College, and were therefore insistent to the point of neurosis that we should not damage the flat in any way (even drawing pins were banned) in case the authorities at St John's might eject them. Living there even for a few months was almost oppressive, so we were grateful to be offered a downstairs flat in a college house in Norham Gardens. Here we stayed for a year or so, with occasional parties thrown in our large lounge, trying not to disturb one of the college tutors who lived above. And here our daughter Karen was born in 1968, not even a toddler when we eventually moved out.

Every so often I would be invited to preach in the parish church, and on one occasion during my first year as a curate, there occurred one of those incidents that causes complete panic for a second until adrenalin takes over. Enoch Powell had fairly recently delivered his "rivers of blood" speech, which was still causing alarm in the country. While preaching about (I think) the Good Samaritan, I mentioned Mr Powell, whereupon Bill Moyes, a normally mild-mannered and respected citizen, rose from his seat, declared in a loud voice that "I didn't come to church to hear party politics!" and stormed out of church, banging the huge mediaeval doors as he went. The silence was audible, until I recovered myself and carried on. Somewhat nerve-shredding at the time, but later Bill and I had a drink together and he confessed the words "Enoch Powell" had woken him up.

Every so often I would be invited to preach in the parish church, and on one occasion during my first year as a curate, there occurred one of those incidents that causes complete panic for a second until adrenalin takes over. Enoch Powell had fairly recently delivered his "rivers of blood" speech, which was still causing alarm in the country. While preaching about (I think) the Good Samaritan, I mentioned Mr Powell, whereupon Bill Moyes, a normally mild-mannered and respected citizen, rose from his seat, declared in a loud voice that "I didn't come to church to hear party politics!" and stormed out of church, banging the huge mediaeval doors as he went. The silence was audible, until I recovered myself and carried on. Somewhat nerve-shredding at the time, but later Bill and I had a drink together and he confessed the words "Enoch Powell" had woken him up.

My second curacy was in Washington Co Durham (CD, not DC!). This was a Group Ministry of five parishes, with an Area of Ecumenical Experiment (AEE - nowadays known as a Local Ecumenical Partnership (LEP)) within one parish - five parishes sharing the work but linked together by formal agreement, with a central Group Council in addition to the Parochial Church Council of each parish. Oxclose was the AEE, in which the CofE and the URC were formal partners. Washington was still being expanded from a series of urban villages into a single New Town, so much of my time was spent visiting newcomers and the recently arrived. One of my chief allies in this was the Community Development Officer from the Development Corporation, who was extremely supportive of my work as I was of his. In NTMA I began to realise the potential for ecumenical working and the sheer joy of discovering how much the various denominations have in common. NTMA conferences were tackling some thorny issues concerning the Church in green field sites, co-operation between denominations at local and at hierarchical levels, and how to ensure continuity of ecumenical posts when an incumbent leaves. In Washington I began to find partnership outside the church more constructive and better understood than inside it. This point will be made again later. The CDO and I worked quite closely in trying to integrate newcomers into Washington, and we shared a lot together about each other's work.

My second curacy was in Washington Co Durham (CD, not DC!). This was a Group Ministry of five parishes, with an Area of Ecumenical Experiment (AEE - nowadays known as a Local Ecumenical Partnership (LEP)) within one parish - five parishes sharing the work but linked together by formal agreement, with a central Group Council in addition to the Parochial Church Council of each parish. Oxclose was the AEE, in which the CofE and the URC were formal partners. Washington was still being expanded from a series of urban villages into a single New Town, so much of my time was spent visiting newcomers and the recently arrived. One of my chief allies in this was the Community Development Officer from the Development Corporation, who was extremely supportive of my work as I was of his. In NTMA I began to realise the potential for ecumenical working and the sheer joy of discovering how much the various denominations have in common. NTMA conferences were tackling some thorny issues concerning the Church in green field sites, co-operation between denominations at local and at hierarchical levels, and how to ensure continuity of ecumenical posts when an incumbent leaves. In Washington I began to find partnership outside the church more constructive and better understood than inside it. This point will be made again later. The CDO and I worked quite closely in trying to integrate newcomers into Washington, and we shared a lot together about each other's work.

In 1976, having been a curate twice and a team vicar once, I went into Industrial Mission. The new Black Country Urban Industrial Mission was being set up across the four boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, West Bromwich and Wolverhampton. There was a vacancy in Dudley, and we moved across in 1976. Over several years the BCUIM team grew to about eight ministers, some part-time, and the BCUIM Council included Anglican, Methodist, United Reformed, Baptist, Roman Catholic and Quaker representatives. This was ecumenism in practice, and I rejoiced in this way of sharing the gifts of our different traditions. It was not always easy - there were tensions about the work we were each doing across the Black Country, but underneath was a strong sense of common ownership of the work.

In 1976, having been a curate twice and a team vicar once, I went into Industrial Mission. The new Black Country Urban Industrial Mission was being set up across the four boroughs of Dudley, Sandwell, West Bromwich and Wolverhampton. There was a vacancy in Dudley, and we moved across in 1976. Over several years the BCUIM team grew to about eight ministers, some part-time, and the BCUIM Council included Anglican, Methodist, United Reformed, Baptist, Roman Catholic and Quaker representatives. This was ecumenism in practice, and I rejoiced in this way of sharing the gifts of our different traditions. It was not always easy - there were tensions about the work we were each doing across the Black Country, but underneath was a strong sense of common ownership of the work.

But visiting a steelworks and three engineering companies every week was far more life-enhancing, and gave me a sense of being grounded in the long-established community of the Black Country, which in the early eighties went through the pain and bereavement that is associated with recession and the closing of places of work. Eventually the steelworks closed, and the site bought as an Enterprise Zone, eventually becoming the Merry Hill shopping mall, known locally then as Merry Hell. I tried hard to persuade the Richardson brothers, who bought the former steelworks, to include a chaplaincy, but while they were supportive of the idea, eventually their economics didn't allow for such an initiative.

But visiting a steelworks and three engineering companies every week was far more life-enhancing, and gave me a sense of being grounded in the long-established community of the Black Country, which in the early eighties went through the pain and bereavement that is associated with recession and the closing of places of work. Eventually the steelworks closed, and the site bought as an Enterprise Zone, eventually becoming the Merry Hill shopping mall, known locally then as Merry Hell. I tried hard to persuade the Richardson brothers, who bought the former steelworks, to include a chaplaincy, but while they were supportive of the idea, eventually their economics didn't allow for such an initiative.

There was - and probably still is - a real problem in understanding the work of Industrial or Workplace Mission, not in workplaces but in the churches. In workplaces, in my own experience, there were few conversations with non-church people about faith in God, but many more about "Church" . This is why I referred to the work of an Industrial Chaplain as in part a public relations exercise among people, many of whom had no experience of church. This was a ministry of accompaniment, walking alongside people at work and trying to understand the things that most concerned them - things like working long hours, the security of their job, the pressure to meet deadlines, whether in a recession their children would find work, and a host of those practical problems that everyone has. I was a sounding board, a neutral counsellor, and, oh! by the way, I'm from the Church. But that was valued by the people we met, who seemed to understand instinctively that the Church would be supportive of them even if they had little idea of how or why that might happen.

There was - and probably still is - a real problem in understanding the work of Industrial or Workplace Mission, not in workplaces but in the churches. In workplaces, in my own experience, there were few conversations with non-church people about faith in God, but many more about "Church" . This is why I referred to the work of an Industrial Chaplain as in part a public relations exercise among people, many of whom had no experience of church. This was a ministry of accompaniment, walking alongside people at work and trying to understand the things that most concerned them - things like working long hours, the security of their job, the pressure to meet deadlines, whether in a recession their children would find work, and a host of those practical problems that everyone has. I was a sounding board, a neutral counsellor, and, oh! by the way, I'm from the Church. But that was valued by the people we met, who seemed to understand instinctively that the Church would be supportive of them even if they had little idea of how or why that might happen.

This job, as a team member of Kent Industrial Mission, was truly an ecumenical appointment. The support I received from each was generous, and for the first few years I spent most Sundays in churches across Kent, talking about the Channel Tunnel and its significance for life and faith. During all this time I was becoming increasingly glad that I was not tied to one denomination and had considerable freedom to travel between churches of different beliefs and traditions. Whilst I recognised that I was able to work only with the Bishop's Licence, and therefore subject to the disciplines of the Church of England, nevertheless in my everyday working I was more aware of serving within the Church of God than within the Church of England.